Share this Post

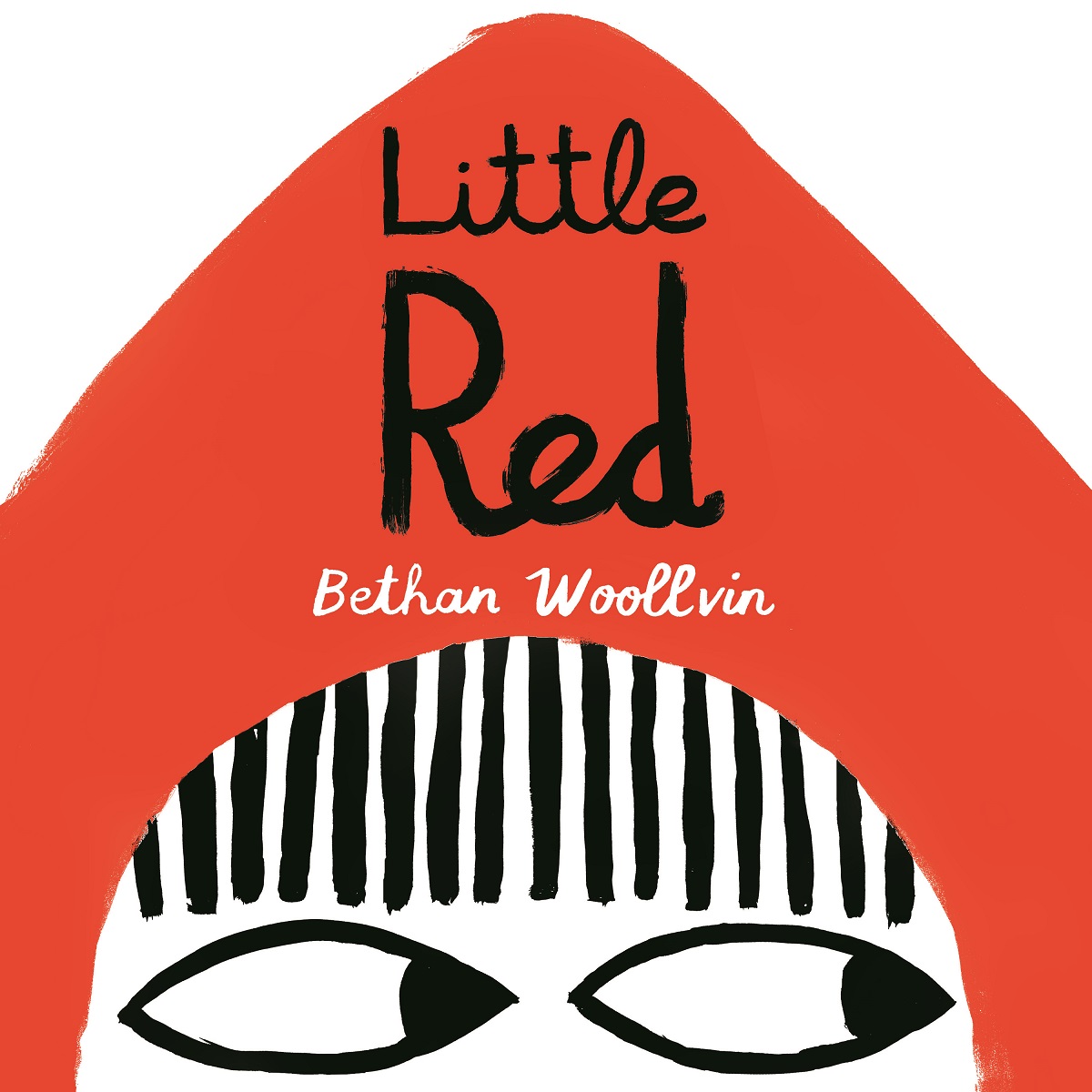

In 1991 picture book author, illustrator, and theorist Molly Bang published a book called Picture This: How Pictures Work, which focuses on how the structural elements of pictures affect readers’ emotions: red is more energetic than blue, diagonals are more threatening than curves, and the placement of objects on the page can indicate the level of safety in the scene. To illustrate her points in Picture This, Bang used the fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood,” and it’s nearly impossible to read Bethan Woollvin’s Little Red without drawing a comparison to some of Bang’s theories.

Color

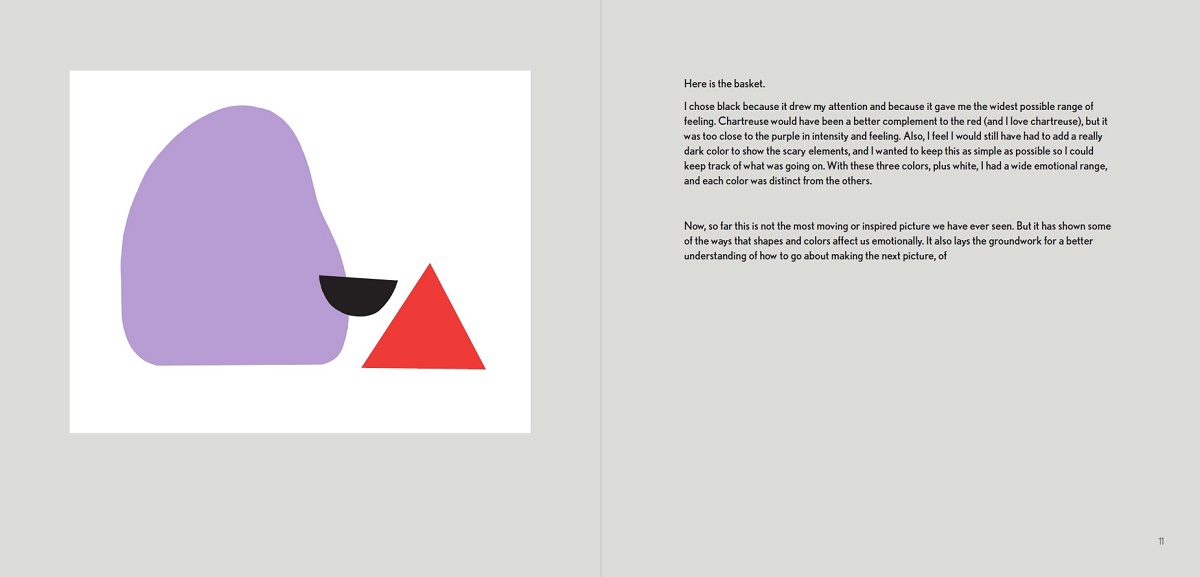

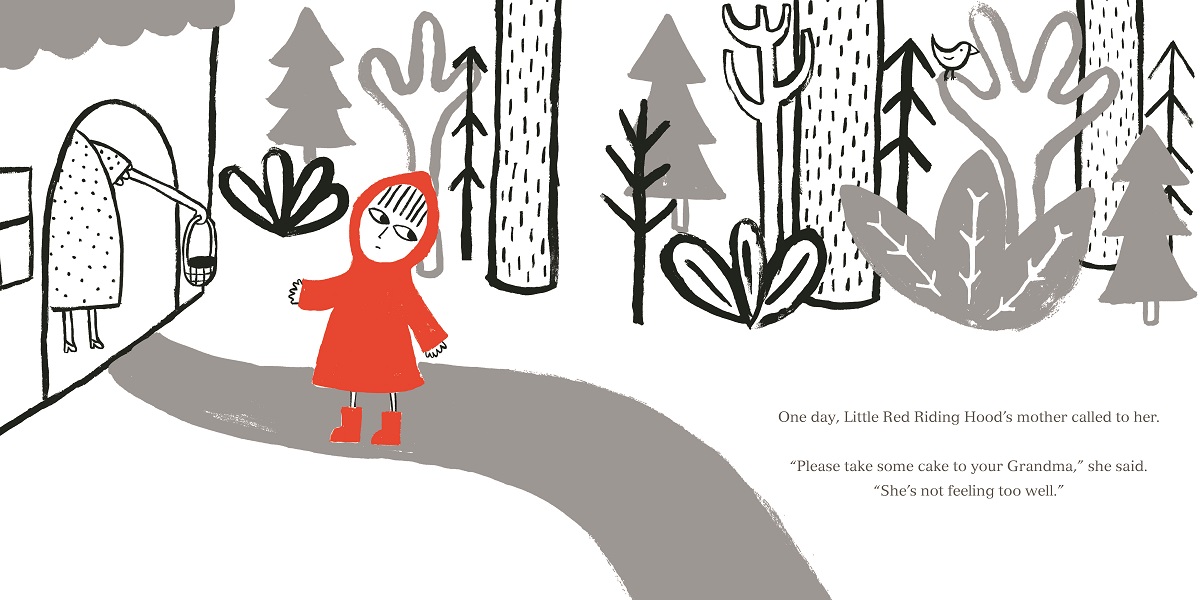

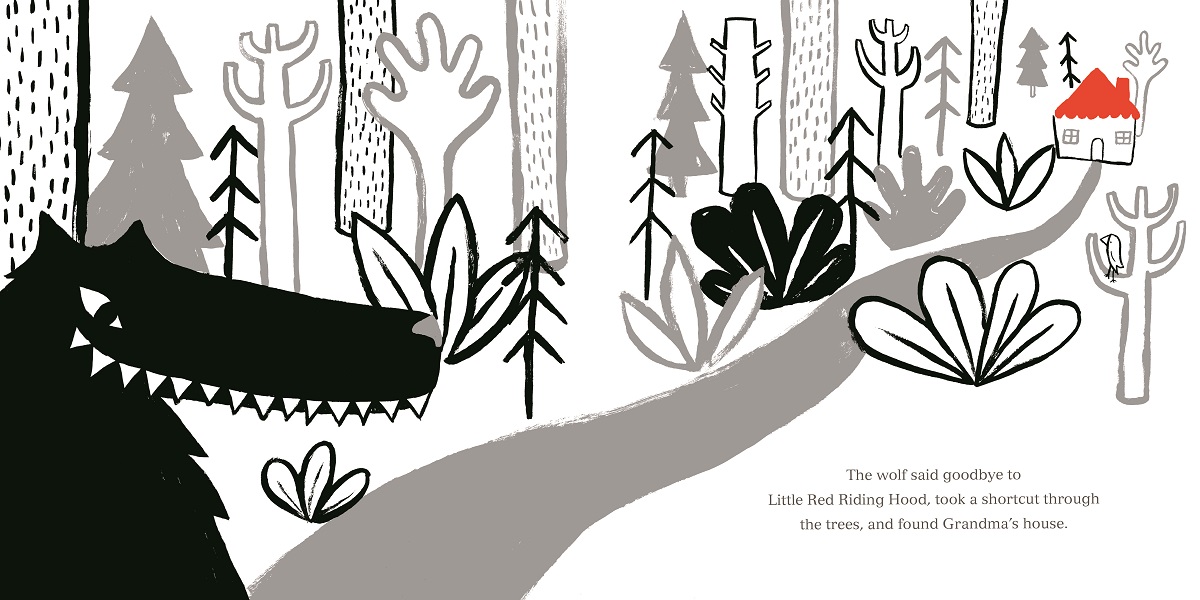

Let’s start with color. Bang suggests using four colors when puzzling out a scene to keep things simple. Woollvin follows suit beautifully in Little Red, using only black, white, red, and gray in her illustrations. This helps draw the eye to very specific points in the story—only Little Red and the objects she uses are red, so we know that it’s a safe color for readers to look to as the story progresses.

This consistency in colors helps us see exactly who owns what part of each illustration. It’s easy for us to visually understand that the tiny house with the red roof is Grandma’s house—we’ve already established that red is reserved for Little Red, so it’s clear that this is her domain. Of course, that only serves to heighten the tension of the image because we see that the Wolf is heading in the same direction.

Angle

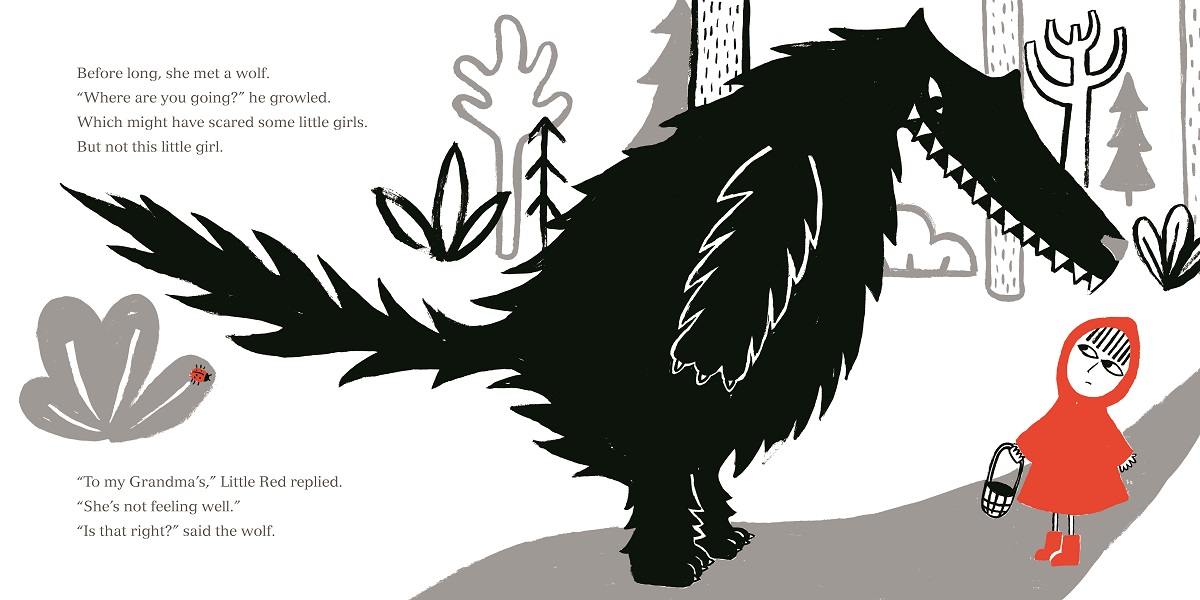

So how do we feel when we see the Wolf—who is notably larger than Little Red—standing over her, essentially pushing her off the page and out of the borders of the book? If the Wolf was standing straight up and not towering over Little Red, would the scene seem as threatening?

The Wolf is essentially pushing Little Red out of the book, barely giving her room to exist in the same space, making the illustration more dynamic and heightening the sense of tension we feel. Will she be able to hold her own? Will she fall prey to the Wolf’s tricks? He very clearly asserts dominance over her in this illustration (and many others)—how will Little Red go about defending herself?

Placement

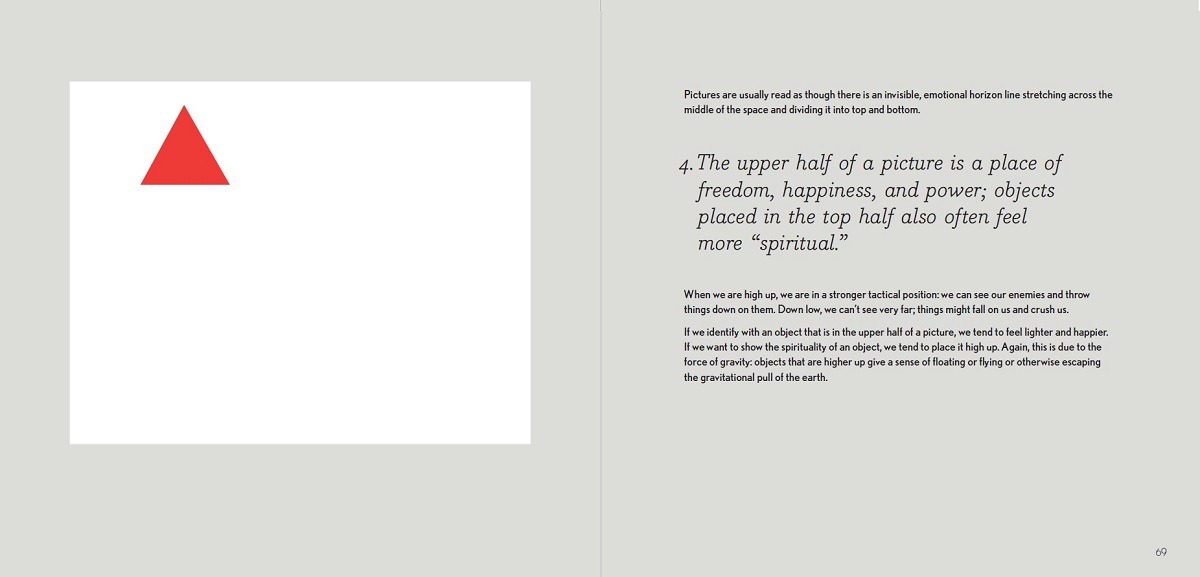

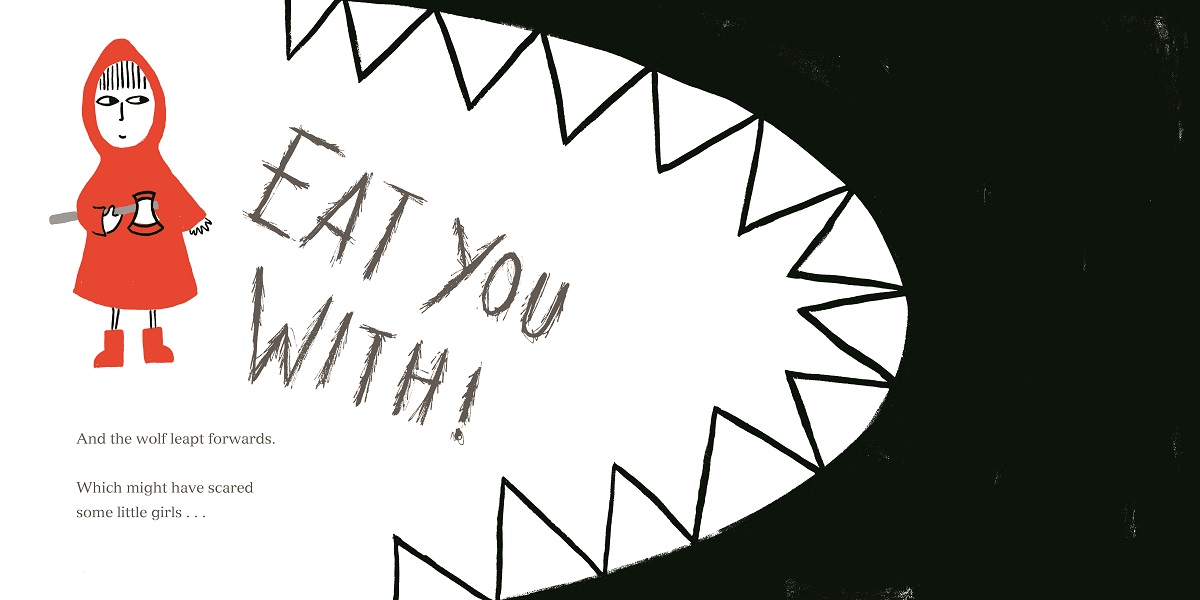

The positioning on the page of Little Red and the Wolf is important. When Little Red confronts an obviously-disguised Wolf, it seems like she is trapped on the left side of the page, unable to safely move to the right side and through the rest of the story. But Bang explains that the upper half of a picture represents “freedom, happiness, and power,” due to its elevated nature. Yes, Little Red is trapped, but she’s almost on an entirely different plane than the Wolf, floating above the danger.

And it doesn’t hurt that she has her ax with her . . .

The intricacies of Molly Bang’s work could never be sufficiently explored here, but reading Bethan Woollvin’s debut picture book and noting just how well she utilizes shapes, placement, and color is illuminating. As part of the Little Red feature, I’m delighted to have co-created a Little Red Story Shapes post that focuses on all of Bang’s theories in the context of Little Red and allows readers to play with Woollvin’s characters to see how the story changes depending on what elements are incorporated. I suggest you grab a pair of scissors and play!

All week long we’re celebrating ALL THE WONDERS of Little Red, and we have so much to share, including a look at fractured fairy tales, how author-illustrator Bethan Woollvin weaves picture book theory into her illustrations, and a school visit in Bethan’s own words.