Share this Post

You DID your job.

You raised a reader!

You snuggled next to your daughter in bed and read The Monster At The End of This Book so many times that you both had every word memorized (and you dreamed of tossing Grover out a window).

You sat on those too-tiny benches at Barnes and Noble and helped your son sound out countless conversations between Elephant and Piggie, even though your back ached and your grande caramel latte went cold.

You spent weekday evenings reading Junie B. Jones and Magic Treehouse aloud with your child, running your finger under the words and trying to stay in the moment, despite the mounting piles of laundry and email you would have to get to after chapter 10.

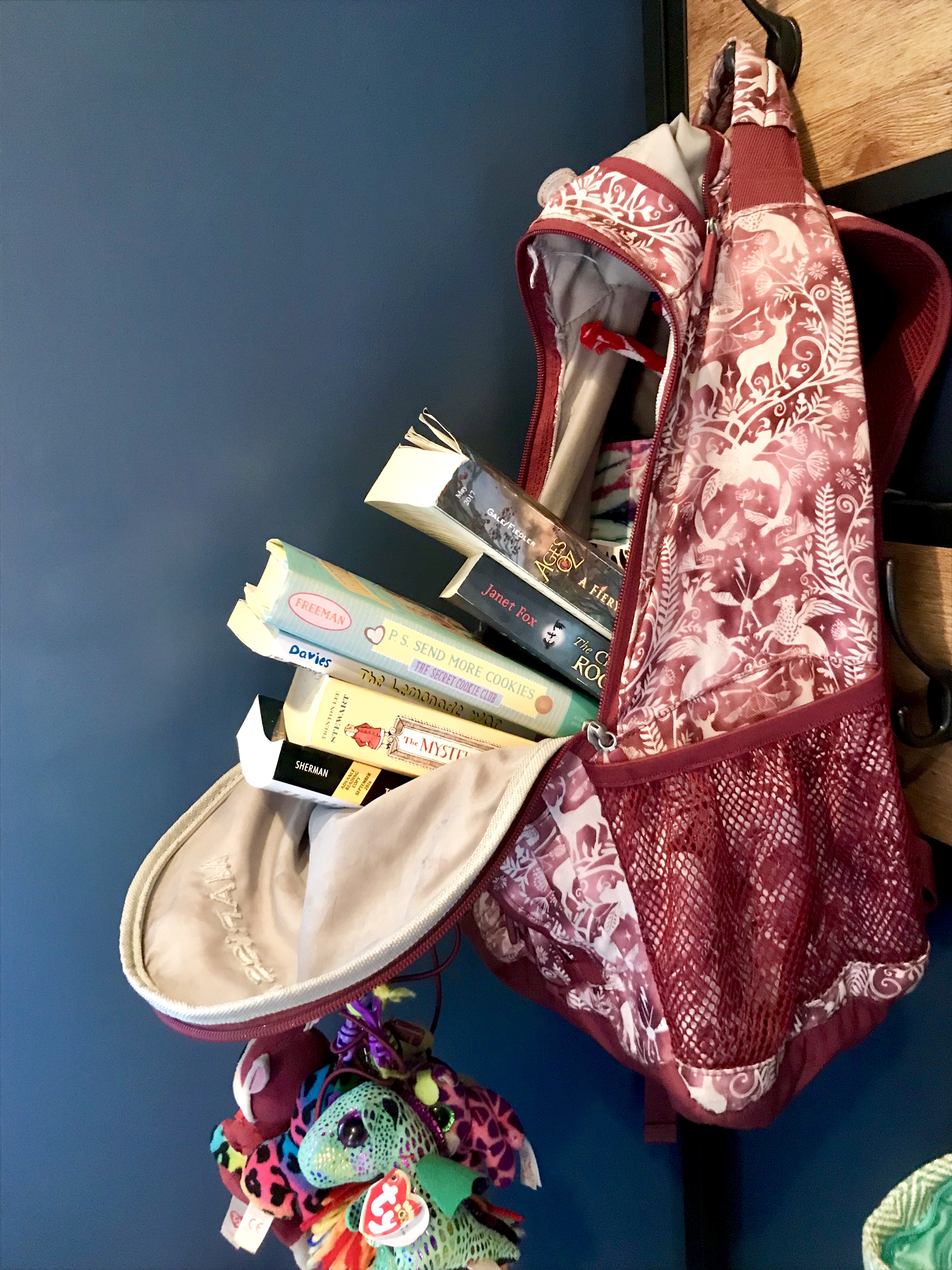

You conferenced with teachers about reading levels and just right books. Found room in the budget for the Scholastic flyers. Dug overdue library books out from under piles of coats and boots.

It took time. It took work. It took frustration, tears, creativity and negotiations—but the day came. Your child was an honest-to-goodness reader, wrapped in all the bright potential you associate with smart, literate, curious children.

And then your reader, your brilliant, wonderful reader…

STOPPED READING.

This was not in the manual. And it was NOT fair.

I know, when this happens, you want to panic. But, instead, take a deep breath. And don’t say goodbye to those bookish grandbabies just yet.

Many kids go through a phase, often in their tweens or teens, when they retreat from reading. For some, it lasts a month or two. For others, years. (I know. You don’t want to hear that. I’m sorry!) But here’s the thing: if you talk to the most bookish adults you know—successful authors, journalists, teachers, librarians (business leaders, lawyers, and cardiologists, too) —many of them went through a time where they didn’t want to read. You can’t force your child to enjoy reading. You CAN support them through this phase and guide them back to a happy, healthy reading life. Here’s how to start:

1. Talk to your child: Let him or her know that you’ve noticed he/she is reading less. Ask if they’ve noticed, and if there’s anything you can do. An acknowledgment of the situation, without judgement or blame, is the best place to start.

2. Understand and address potential causes: Often, kids retreat from pleasure reading due to completely understandable stressors—such as a heavy workload from school, lots of assigned reading and busy extracurricular schedules. They may find more and more of their free time absorbed by changing social opportunities/interests, a first job, or engrossing digital options for entertainment. Perhaps your child’s middle or high school doesn’t have scheduled library visits the way elementary school did, and he hasn’t adjusted to having to seek out reading materials unprompted.

You can take steps to problem solve with your child—but be aware that, in some cases, the best solution is to respect that your child doesn’t have time and energy for everything. You can sympathize, right? Agree to check in again in a month or two and see if anything has changed.

NOTE: Any substantial change in a child’s behavior should be investigated to be certain there aren’t underlying causes that require more attention. A change in reading habits can be caused by fatigue, headaches, changes in vision, learning disabilities, social pressure, depression, or other serious issues. If you feel physical, emotional, mental health or developmental concerns are affecting your child, talk to him or her openly, and address your concerns with qualified professionals.

3. Provide opportunities to connect with reading materials in low-pressure ways. Playing an audiobook in the car or kitchen, leaving high-interest magazines on the breakfast table (or in the bathroom!), or making an unscheduled stop at the comic book store on the way home from soccer practice all encourage reading without coming across as nagging or pressuring. Watching movies based on books or finding books about movies you enjoyed is a great tactic, too. Remember that instruction manuals, recipes, signage in museums, and sports statistics are all valid reading options—among many others.

4. Read together! Consider asking your child to pick a book for you both to read (together or separately) and discuss. Shared reading and conversation strengthen relationships, and give you an opportunity to show that you respect and value the reading material your child chooses. You could also take turns reading from joke books, poetry, or science facts—perhaps making it part of your daily routine. Engage your child in looking for online articles on subjects that interest you both, whether that’s cute animal rescues, spies and espionage, or celebrity gossip.

5. Don’t judge: Placing restrictions on what, where, when and how your child reads makes it a chore—or worse, a punishment. My teenager is currently obsessed with reading serial horror novels on Wattpad right before bedtime—and though I take exception to her plan for SO MANY reasons, I just keep telling her “I’m so happy to see you reading.” (At which point she rolls her eyes at me.)

6. Be Open About It: You might be feeling stressed that your child isn’t reading. You might be worried that teachers and other parents are going to judge your child—or you—if they find out. Schools can be pretty competitive, and so can the parental conversations at band practice pick-up. Do not be ashamed or worried that you are a bad parent or that there is something wrong with your child. Sharing your experience with trusted friends and teachers may open up doors to support and to ideas that work well for you, your child, and your family.

7. Model a Reading Life: Your kids follow your lead (even if it doesn’t always seem like it). Let your kids know that there have been times in your life when you were too busy to read for pleasure, or you couldn’t find anything that interested you, or you only read Far Side Comics—and then let them see you read.

It can be a surprise, a stressor, and a disappointment for parents when readers back away from books—but you are not alone and your child is not going to suffer permanent, negative consequences. There’s plenty you can do to support your child and ensure that, sooner or later, he or she finds the way back to reading.